POLS 1140

Ideology and Issues

Updated Mar 9, 2025

Wednesday

Plan for the Week

Wednesday

- Finish up Converse (1964)

- Begin:

- Survey groups assigned (will update today)

Friday

- No class

- I’ll record some comments on material we haven’t covered

Groups

Review

- Election forecasting is both art and science

- Hard to predict direction of polling errors

- Models are complicated / transparency is key

- Converse (1964)

- Explore the degree of ideological constraint in the American public

Using polls to forecast elections

Forecasting Elections

Election forecasts reflect varying combinations of:

- Expert Opinion

- Fundamentals

- Polling

Forecasts differ in the extent to which they rely on these components and how they integrate them in their final predictions

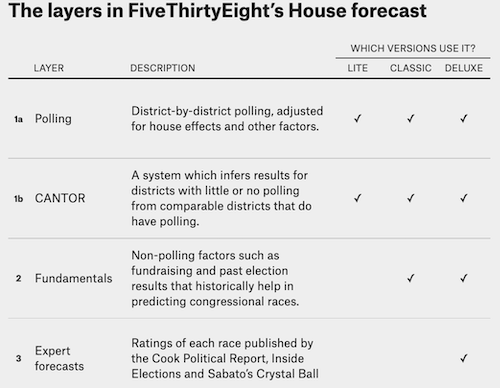

FiveThirtyEight’s Approach to Forecasting

Under Nate Silver…

Forecasting Elections with Polls

The preeminence of polling in modern forecasts reflects the success of Nate Silver and FiveThirtyEight in correctly predicting the 2008 (49/50 states correct) 2012 (50/50) presidential elections

Any one poll is likely to deviate from the true outcome

Averaging over multiple polls

the polls aren’t systematically biased

Concerns about the polls reflect the failure of such approaches to predict

Trump’s Victory in 2016

Strength of Trumps Support in 2020

Polling in Recent Elections

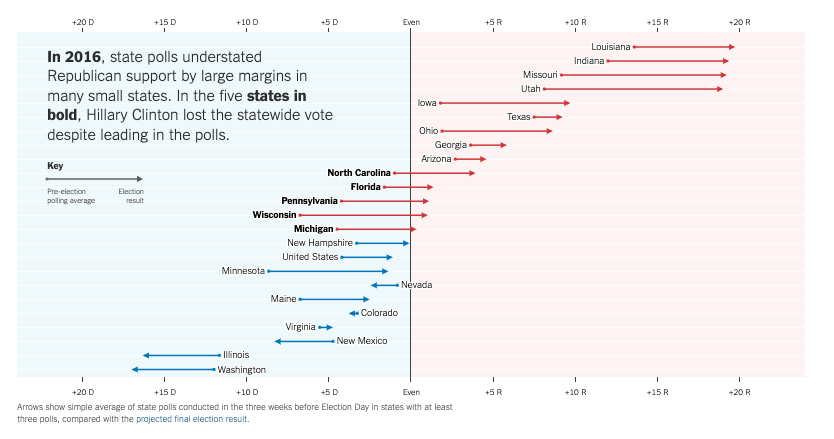

Polling the 2016 Election:

- The polls missed bigly

- National polls were reasonably accurate (Clinton wins Popular Vote)

- State polls overstated Clinton’s lead / understated Trump support

How did we get it so wrong in 2016?

Some likely explanations

Likely voter models overstated Clinton’s support

Large number of undecided voters broke decisively for Trump

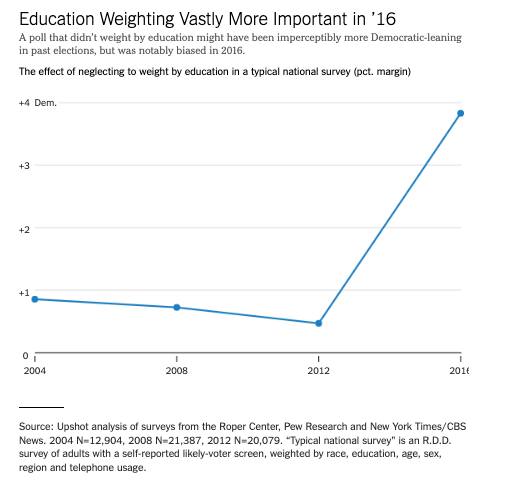

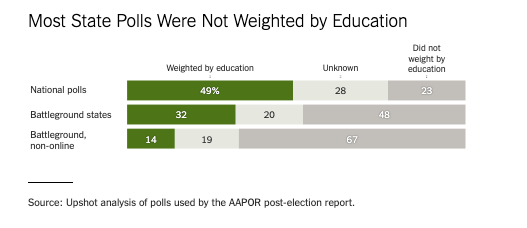

White voters without a college degree underrepresented in pre-election surveys

Weighting for education

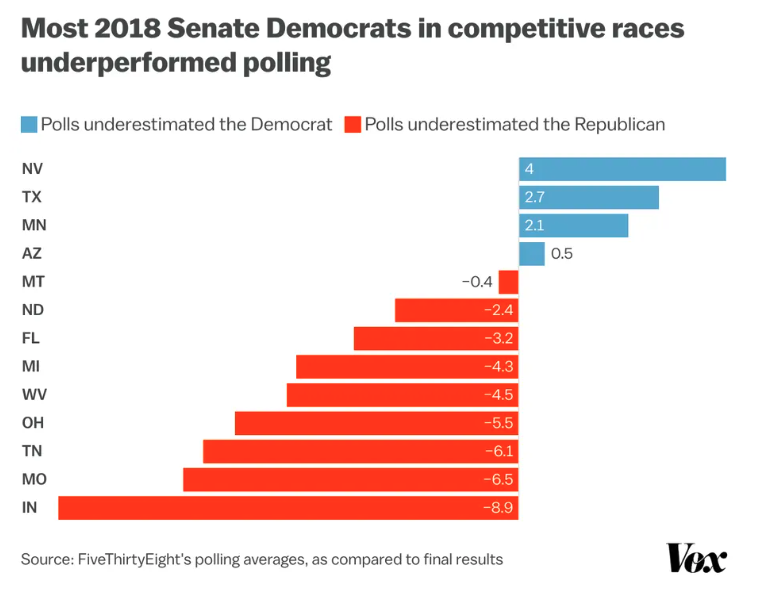

2018: A brief repreive?

Polls did a better job

- Most state polls weighted by education

- Underestimated Democrats in House and Gubernatorial races

- No partisan bias in Senate Races

Forecasts correctly call:

- Democratic House

- Republican Senate

However…

2020: Historic Problems, Unclear Solutions

Average polling errors for national popular vote were 4.5 percentage points highest in 40 years

Polls overstated Biden’s support by 3.9 points national polls (4.3 points in state polls)

Polls overstated Democratic support in Senate and Guberatorial races by about 6 points

Forecasts predicted Democrats would hold

- 48-55 seats in the Senate (actual: 50 seats)

- 225-254 seats in the House (actual: 222 seats)

2020: What Went Wrong

Unlike 2016, no clear cut explanations for what went wrong

Not a cause:

- Undecided voters

- Failing to weight for education

- Other demographic imbalances

- “Shy Trump Voters”

- Polling early vs election day voters

Potential Explanations

- Covid-19

- Democrats more likely to take polls

- Unit non-response

- Between parties

- Within parties

- Across new and unaffiliated voters

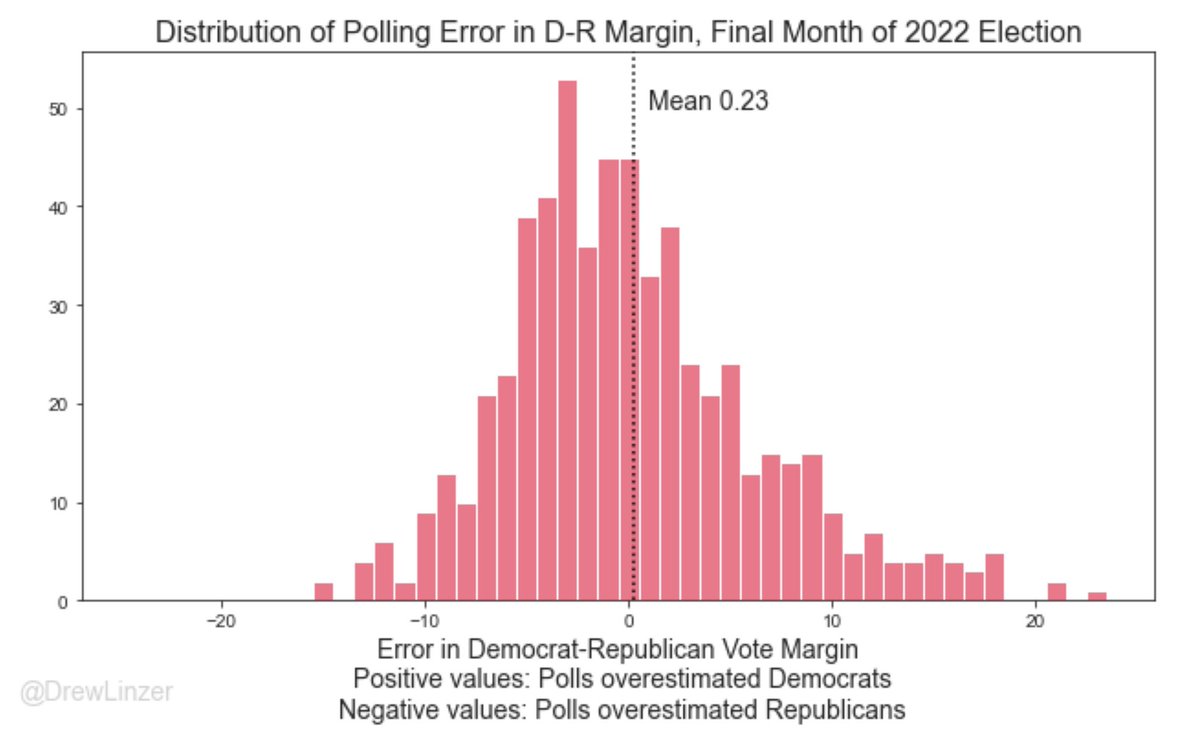

How the polls did in 2022

Overall, pretty good

Average error close to 0

Average absolute error ~ 4.5 percentage points

Some polls tended overstate Republican support (e.g. Trafalgar)

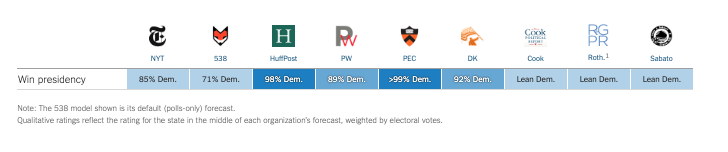

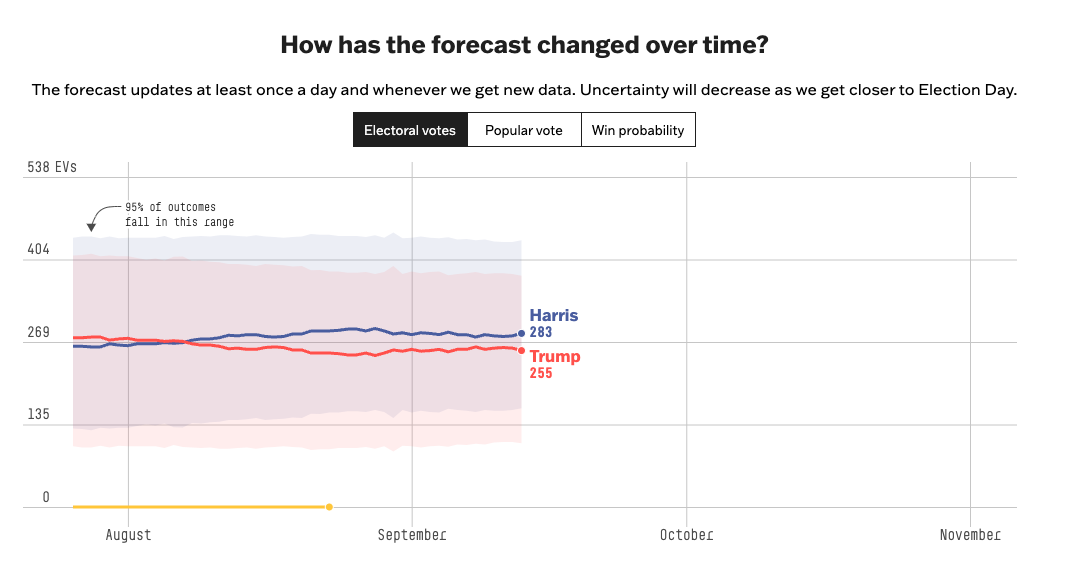

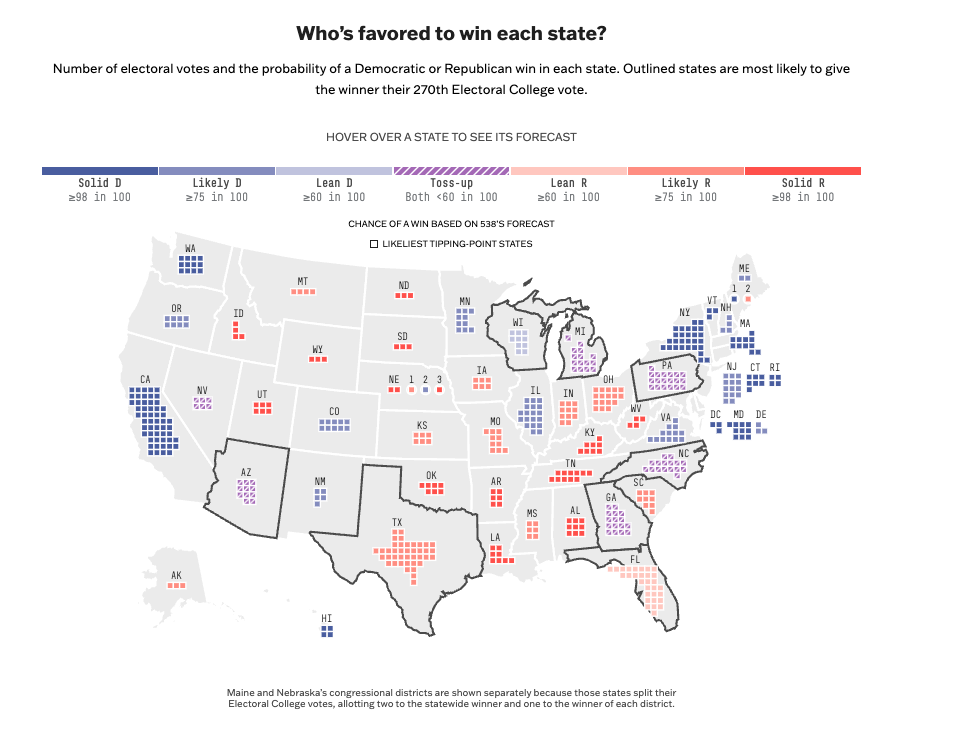

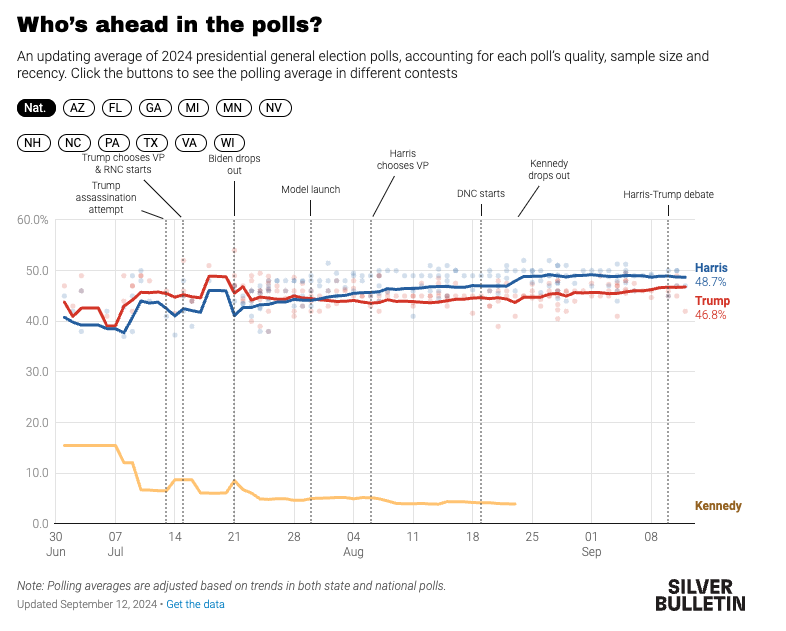

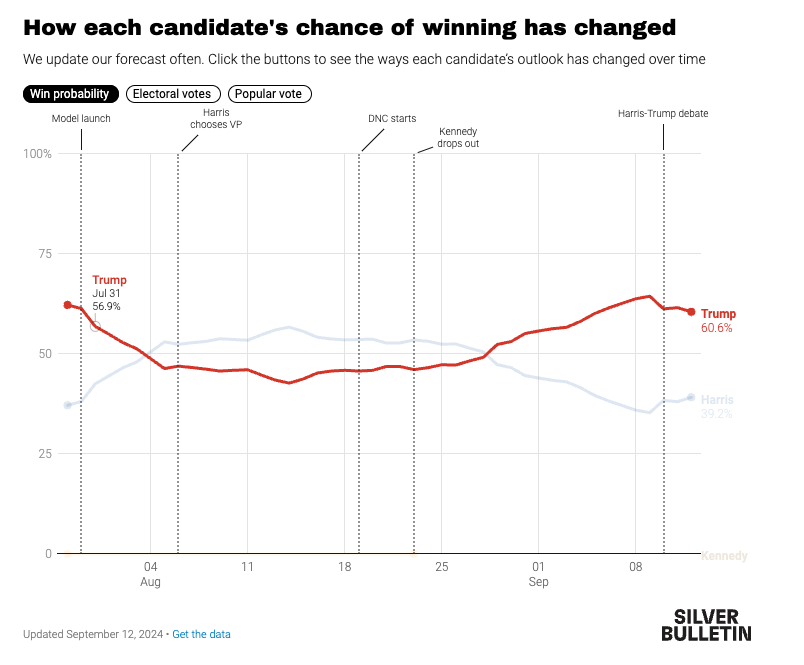

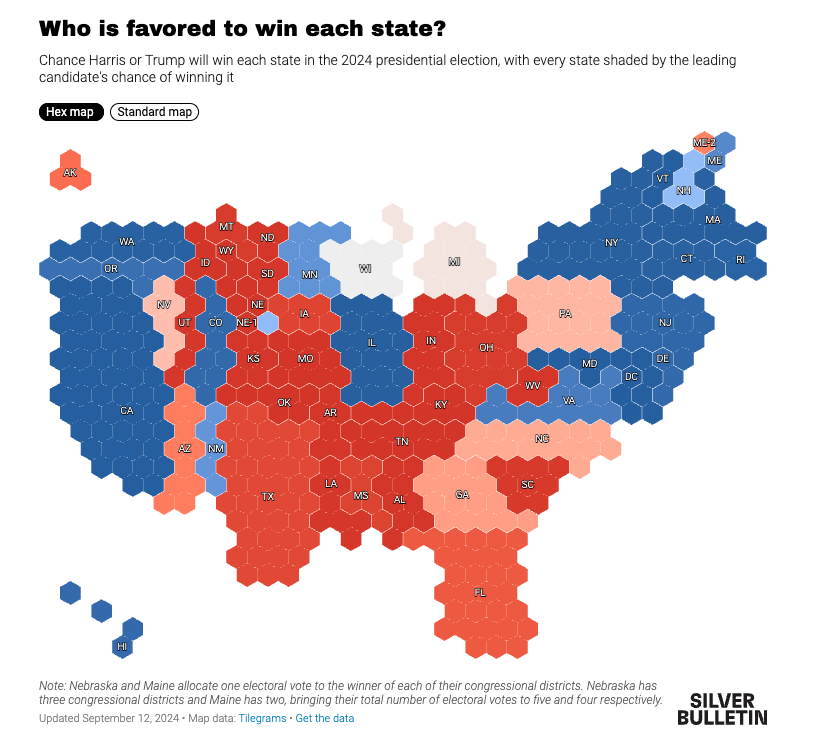

What do the polls say for 2024

Harris 2-3 point lead in popular vote

Math of electoral college favors Republican candidates

Polls will be wrong, but hard to predict the direction of the error (this is a good thing)

A lot can happen

Different:

- Polls

- Weighting of fundamentals and polls

- Different modeling assumptions (How to model convention bumps)

Who’s right?

Converse (1964)

Goals

This weeks readings are HARD

Our goal is to answer the following:

- What’s the research question

- What’s the theoretical framework

- What’s the empirical design

- What’s are the results

- What’s are the conclusions

The Structure of Converse (1964)

- Introduction

- Some Clarification of Terms

- Sources of Constraint on Idea Elements

- Active Use of Ideological Dimensions of Judgement

- Recognition of Ideological Uses of Judgement

- Constraints among idea-elements

- Social Groupings as central objects in belief systems

- The Stability of belief elements over time

- Issue Publics

- Summary

- Conclusion

Introduction

Converse introduces the concept of belief systems and tells us this article is about the contrast between the belief systems held by political elites and the mass public

He gestures towards a hierarchy of belief strata and the importance of belief systems for democratic theory

Kind of slow start

Some Clarification of Terms

Converse defines his core concepts

Beliefs Systems

Idea elements

Constraint:

- The interdependence of ideas in a belief system

- A sense of what goes with what

Centrality:

- How likely a belief is to change?

Range:

- The diversity of topics

Sources of Constraint

(Theoretical Framework)

Converse lays out some plausible sources of ideological constraint:

Logical: More spending + Less taxes -> Bigger deficits

Psychological: “the quasi-logic of cogent arguments”

Social: Social diffusion of information -> creates perceptions of what goes with what

Converse also offers a definition of the well-informed person who understands what goes with what but can also articulate why.

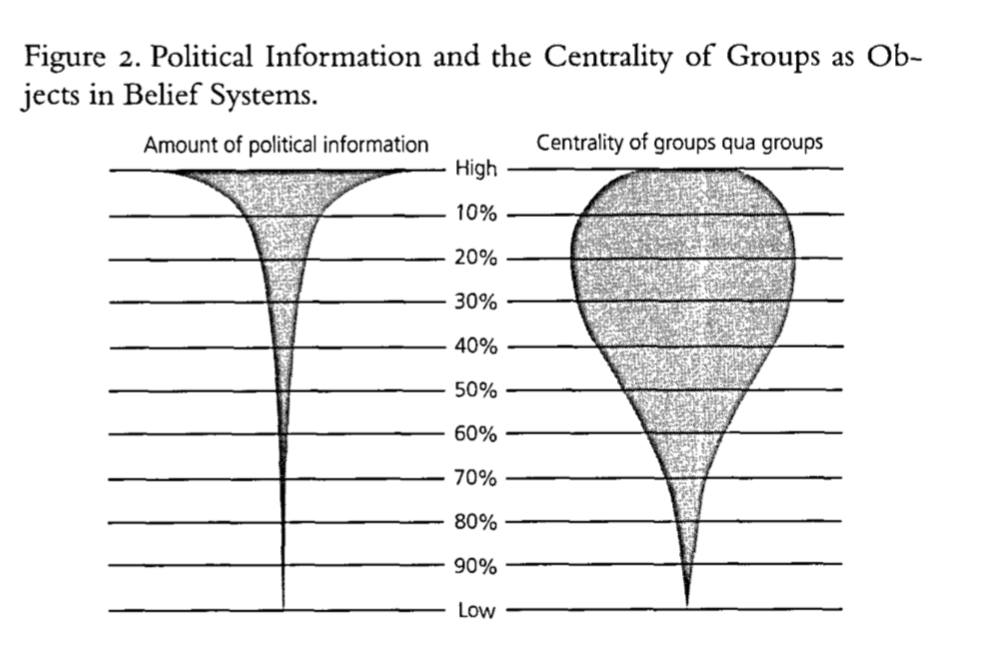

Consequences of declining information belief systems

Converse argues as we move from the well-informed to uninformed, several things happen:

- Belief systems lose constraint

- Social groups replace ideology principles in centrality

So how does he go about doing showing this?

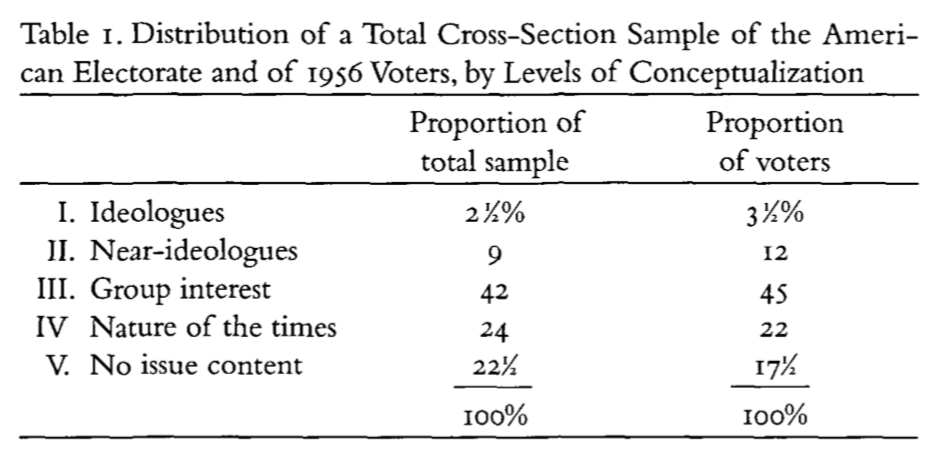

Active Use of Ideological Dimensions of Judgement

Converse considers people’s open-ended responses to questions about whether there is anything they like or dislike about presidential candidates in 1956 and the political parties discussed in detail in chapter 10 of the The American Voter

Active Use of Ideological Dimensions of Judgement

The American Voter

Ideologues:

Well, the Democratic Party tends to favor socialized medicine and I’m being influenced in that because I came from a doctor’s family.

Group Benefits:

Well I just don’t believe their for the common people

Nature of the times:

My husband’s job is better. … My husband is a furrier and when people get money they buy furs

No Content:

I hate the darned backbiting

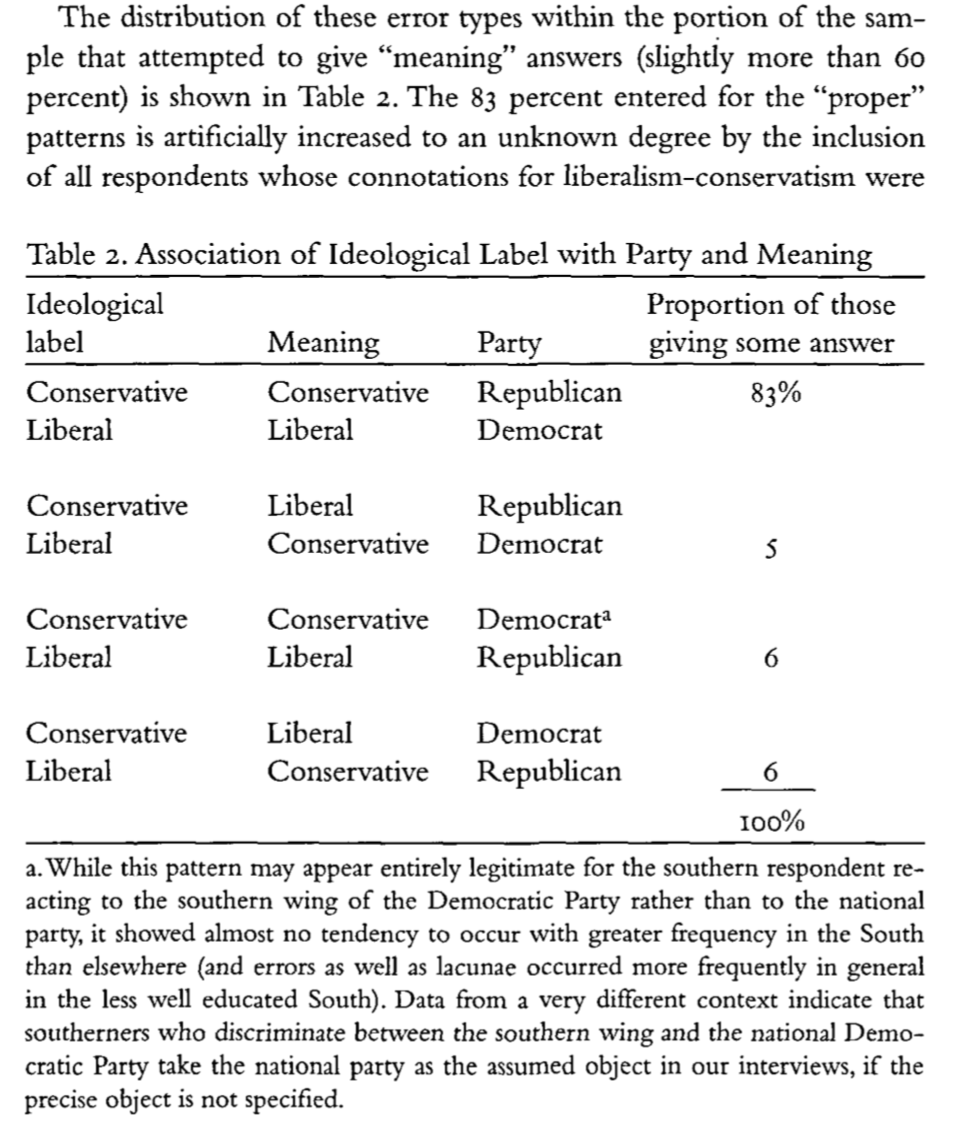

Recognition of Ideological Dimensions of Judgement

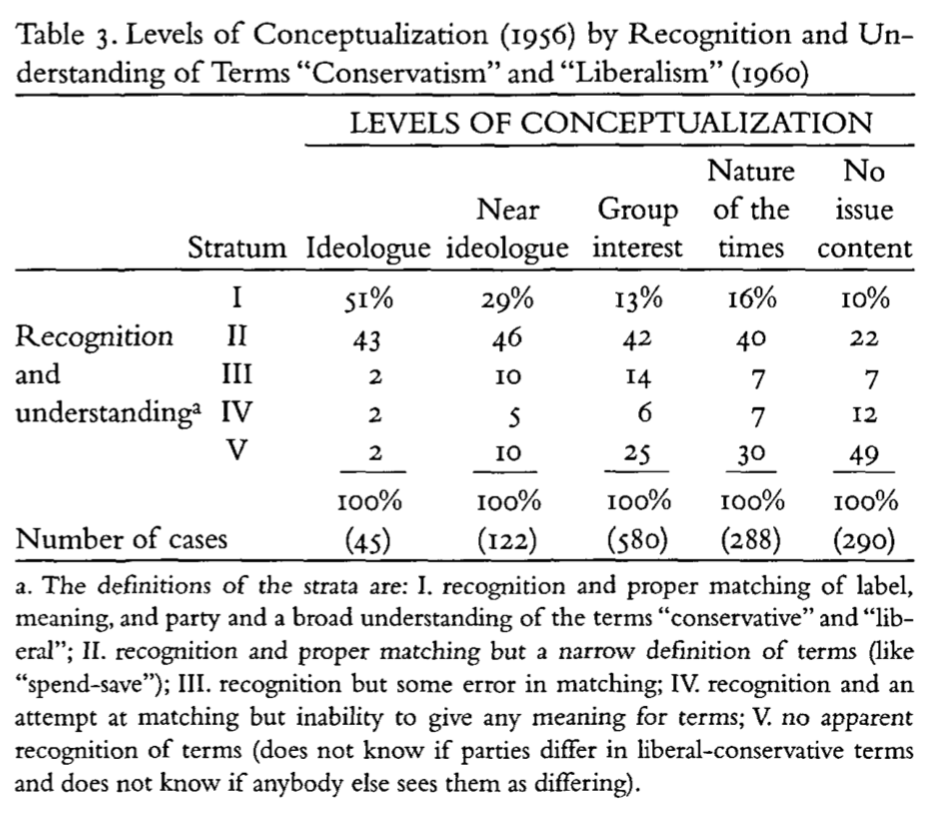

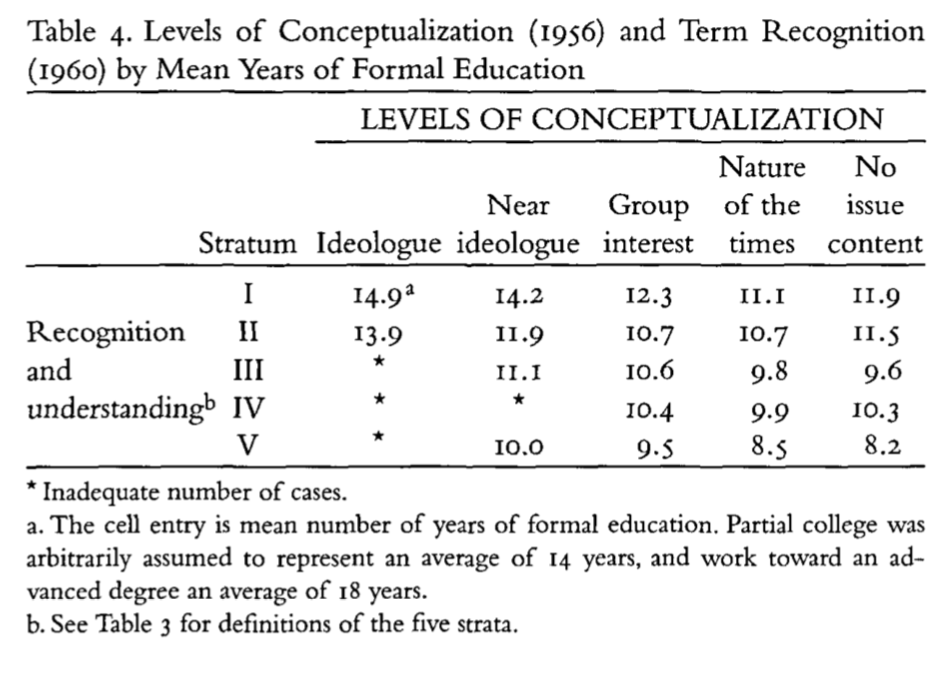

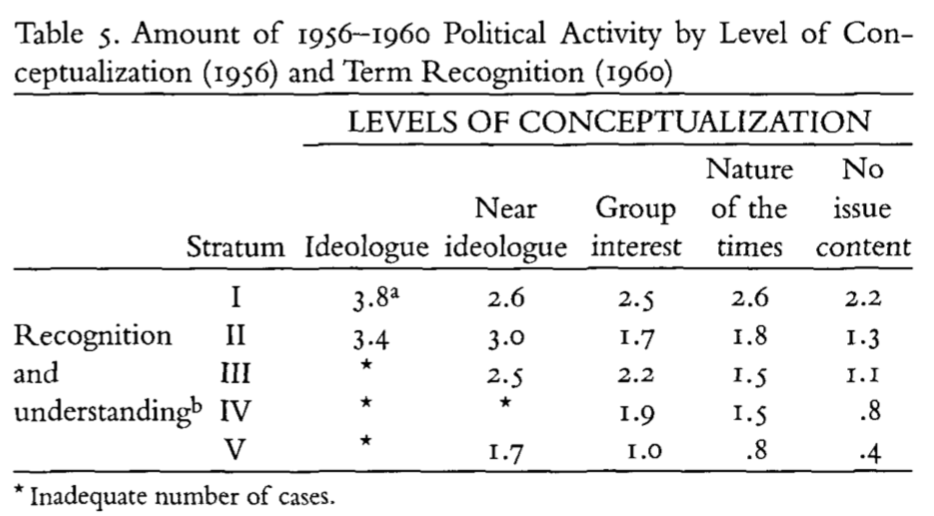

Next Converse considers these levels of conceptualization in 1956 with peoples ability to attach the correct ideological labels with political parties

Overall, most respondents label Democrats as the liberal and Republicans as the conservative party (Table 2)

But the depth of this understanding appears quite shallow (e.g. spend vs save) (Table 3)

Recognition varies with education (Table 4)

Those with greater levels of recognition are more active in politics (Table 5)

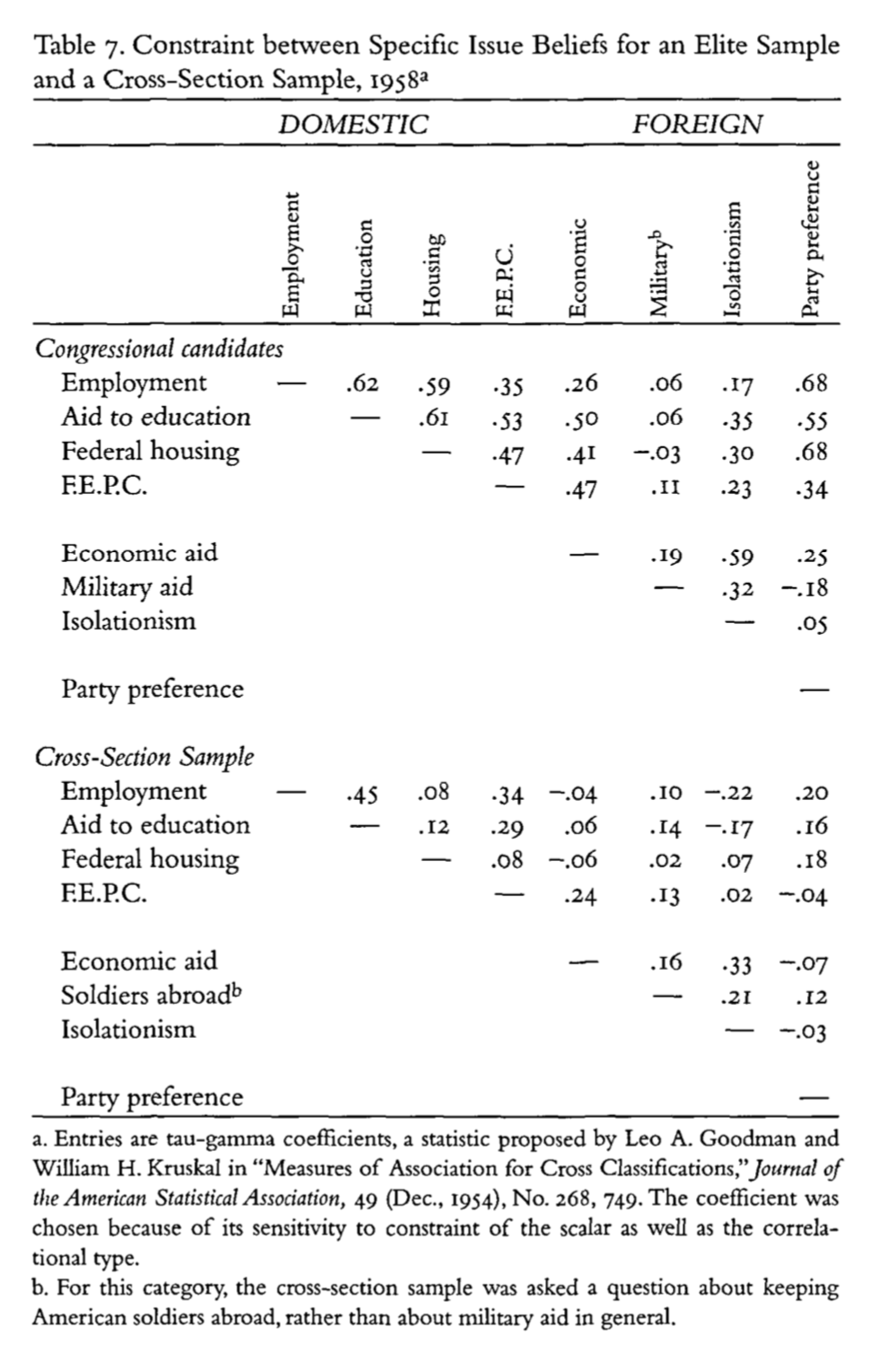

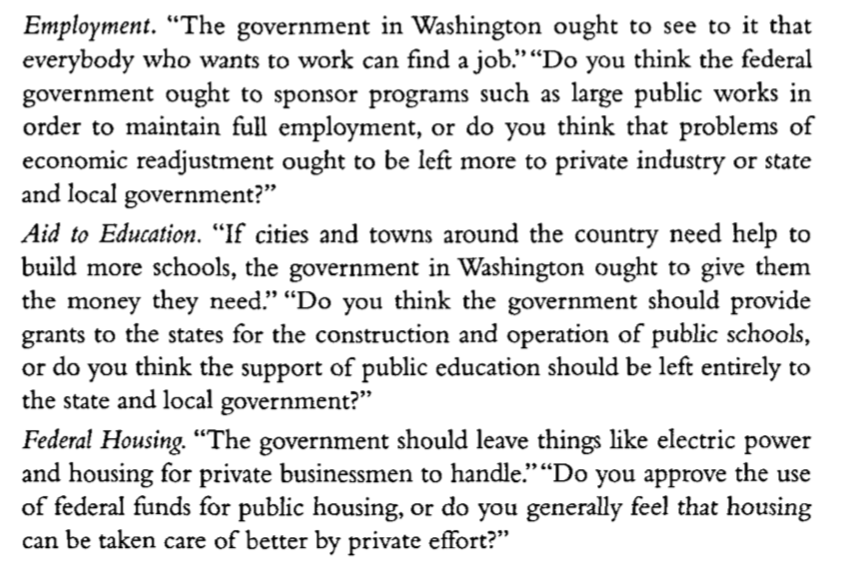

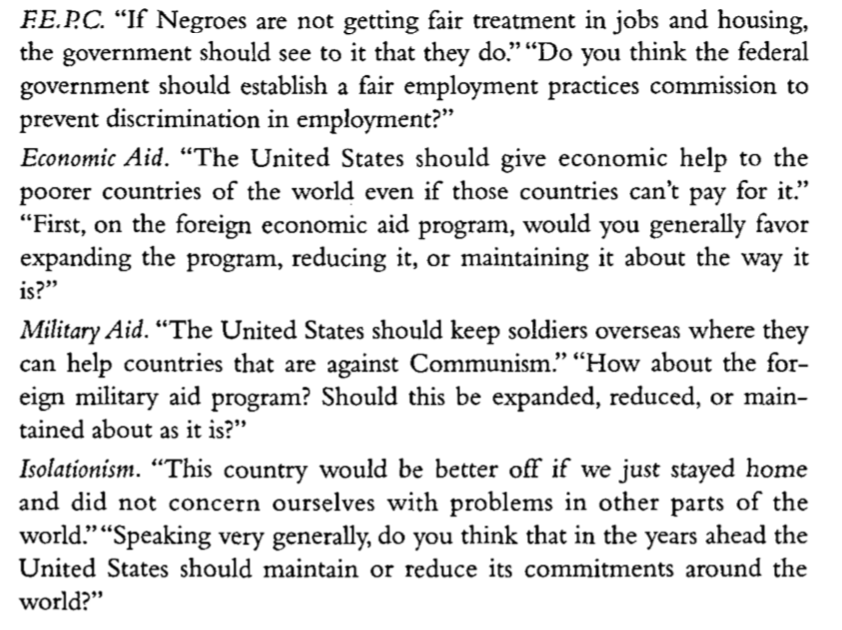

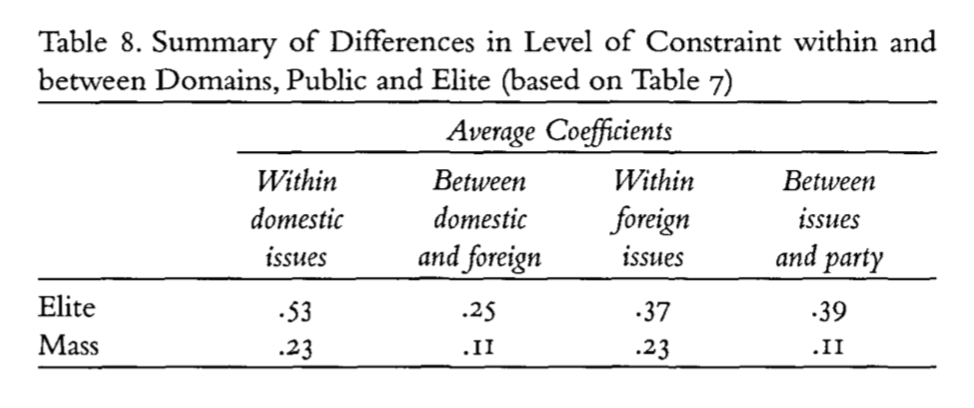

Constraints among idea-elements

Next Converse considers the degree of constraint (measured by correlations) between issue elements in an elite (congressional candidates) compared to the mass public

People who took a liberal position on one issue did not necessarily take a liberal position on another

the correlations between between elites’ issue attitudes were higher than the mass public

Individuals lack a sense of what goes with what

What are these measures

Read the footnotes!

What are these measures

What’s a tau-gamma coefficient?

I believe Converse is using a measure of association for ordinal data that’s built off the cross tabs of variables. The estimate of gamma,

where “ties” (cases where either of the two variables in the pair are equal) are dropped. Then

Note

As long as you have a basic sense of what correlations are trying to tell us you don’t need to know the technical details of a specific estimator

Elites show higher degrees of constraint

Social groupings as central objects in belief systems

The stability of belief elements over time

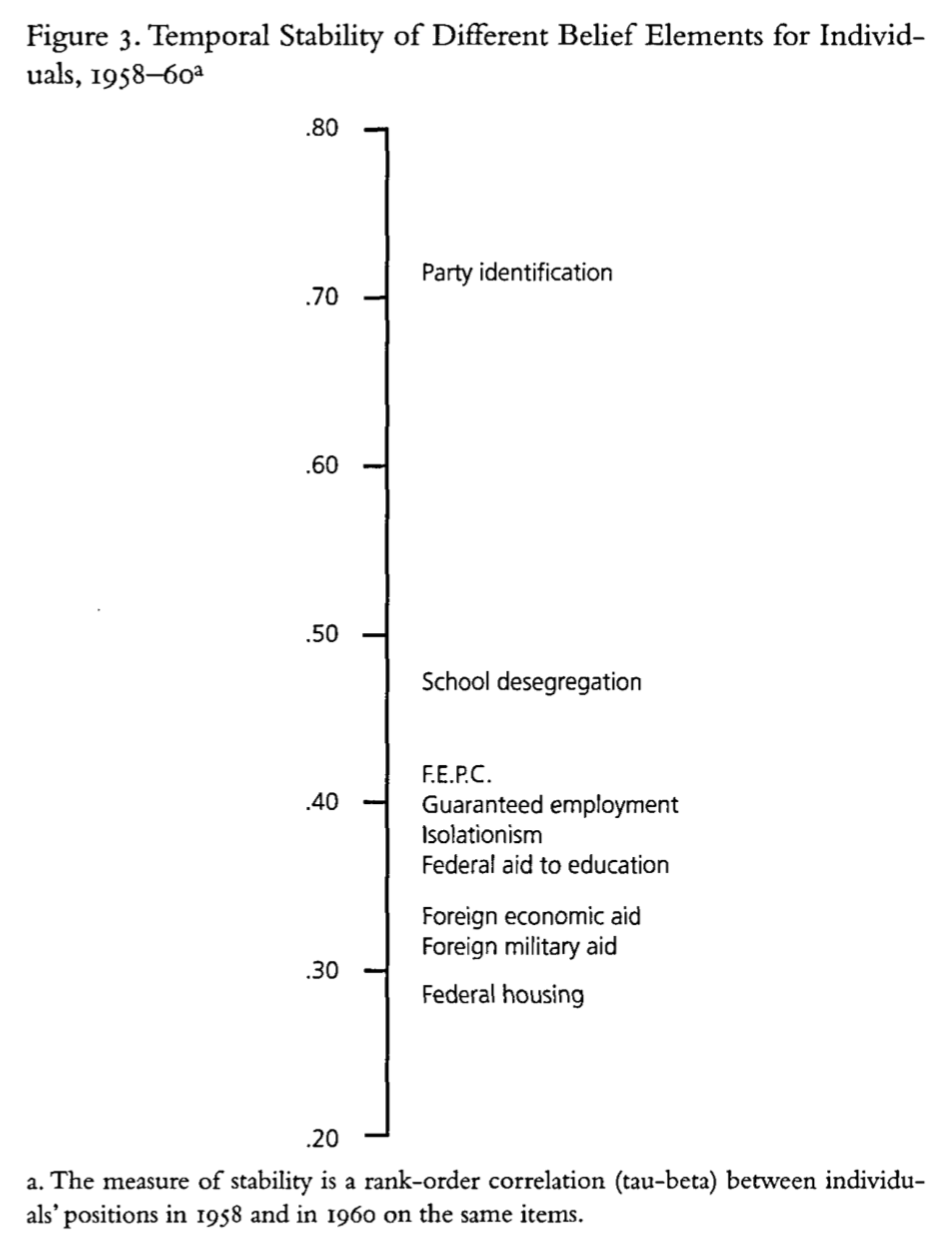

Converse considers the stability of responses over time, looking at data from 1958-1960 finding variation the strength of temporal correlations across surveys, and attributes this to the centrality of groups and the party system for the mass public

The stability of belief elements over time

The final piece of Converse’s argument concerns the stability of a single belief over time (1956, 1958, 1960):

The government should leave things like electrical power and housing for private businessmen to handle

A limiting case an issue not in the public debate of this period

People appear to answer the question at random

Only a small proportion (~20% fn. 39) held stable attitudes across all three periods

Issue Publics, Summary, Conclusion

Converse wraps up his argument by

Allowing for the possibility of small “issue publics” on more narrow issues

Offering some comments on cross-national and historical comparisons

Summarizing the “continental shelf” that exists between elites and masses.

What do we think?

- What’s the research question

- What’s the theoretical framework

- What’s the empirical design

- What’s are the results

- What’s are the conclusions

Summary of Converse (1964)

Converse (1964) remains one of the most influential articles in American Political Behavior

Framed decades of research on questions of ideology and citizen competence

- Why?

In the absence of coherent and stable worldviews, how does democracy function?

Responses to Converse (1964)

Responses to Converse (1964)

- Measurement error (Today)

- Revised definitions of citizens competence (Next Week)

- The Miracle of Aggregation

- Source Cues and Heuristics (Weeks 5 and 6)

- Revised models of Survey Response (Weeks 5 and 6)

- Revised models of what democracy requires (on going)

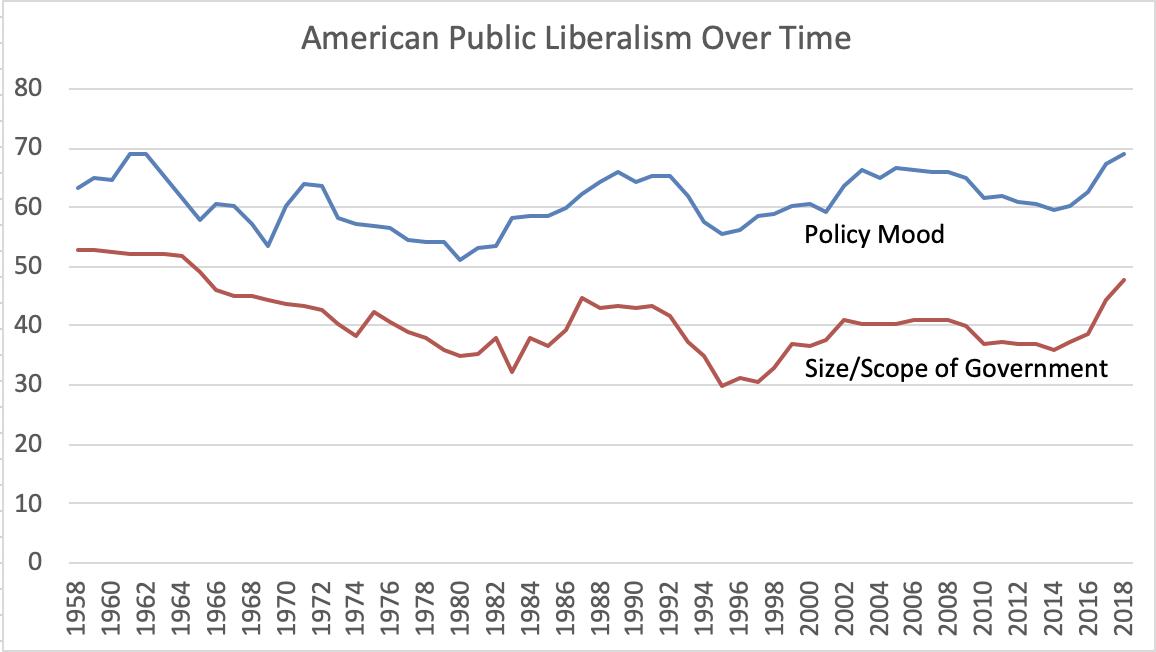

The Miracle of Aggregation

Responses to Converse (1964)

- Measurement error (Today)

- Revised definitions of citizens competence (Next Week)

- The Miracle of Aggregation

- Source Cues and Heuristics (Weeks 5 and 6)

- Revised models of Survey Response (Weeks 5 and 6)

- Revised models of what democracy requires (on going)

Class Survey

Please click here to take our periodic attendance survey

Ansolabehere et al. (2008)

What’s the research question

- Are issue preferences as unstable and incoherent as Converse suggests, or can accounting for measurement error reveal a more ideologically consistent mass public

What’s the theoretical framework

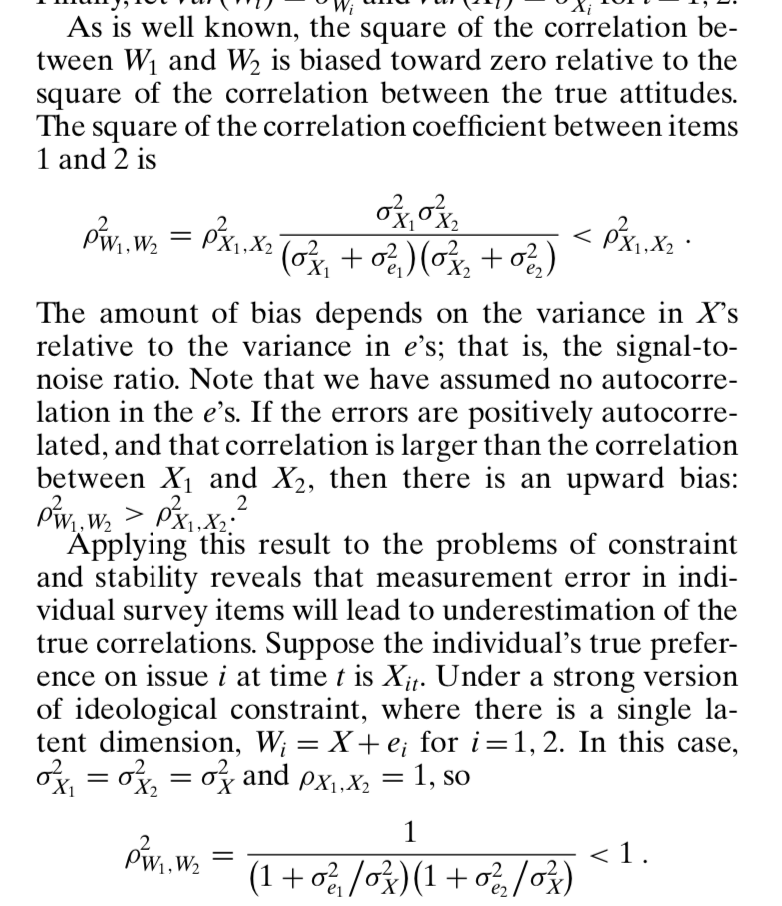

Ansolabehere et al. pick up a critique made by Achen (1975) and others that the lack of constraint is primarily caused my measurement error

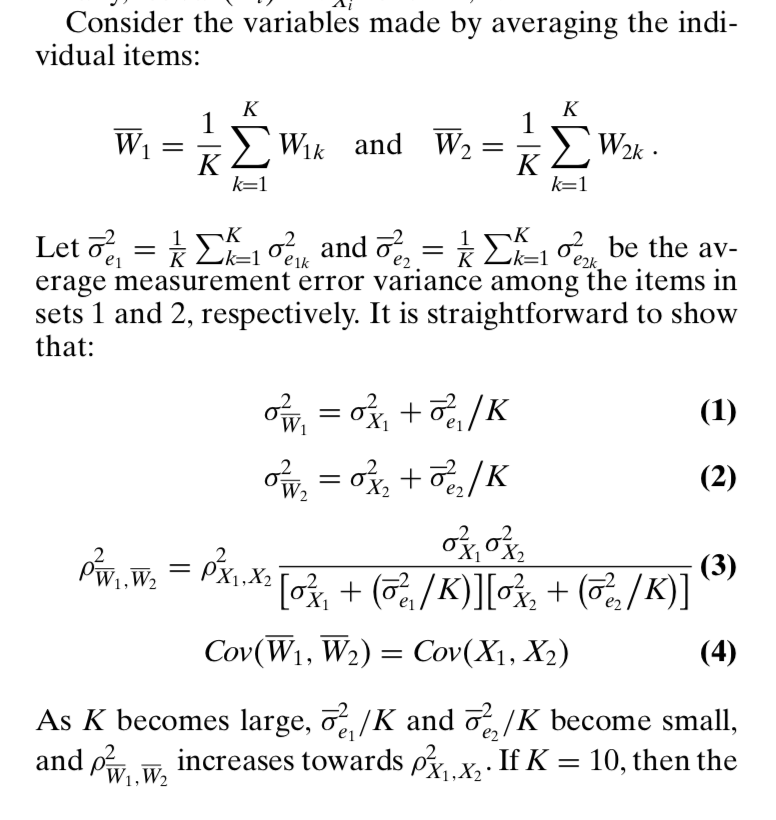

They show that measurement error tends to decreases with the number of items one uses

They offer a simple solution measure concepts scales constructed from multiple items

Measurement Error

Classic measurement error models assume what we observe is a measure of some unobserved (latent) truth, plus measurement error that has mean 0 and is uncorrelated with the latent truth, X.

Measurement Error

One can show that:

And the covariance between our observed and unobserved variables is:

Correlations and Reliability

With some assumptions and transformations we can show that the square of correlations describe the reliability of a measure

Reliability is the proportion of the variance in the observed variable that comes from the latent variable of interest, and not from random error.

This motivates Ansolabehere et al. approach

Correlations and Reliability

Measurement error reduces reliability

Multiple items reduce measurement error

With some caveats

- No autocorrelation

- Error on one item doesn’t predict error on another

- Additional items can’t be too noisy

What’s the empirical design

Panel data from the NES

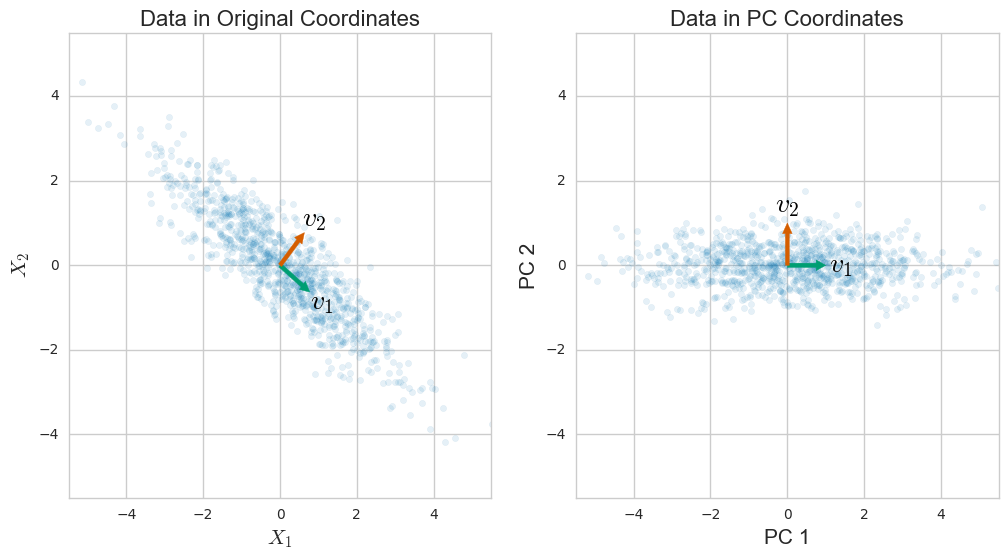

Principal component factor analysis to scale items together

- Basically averaging (weighting by the variance each item contributes)

Correlational analysis within items and across time and also within surveys

Simulations

Sub-group analysis by political sophistication

Regression analysis of issue voting

Principal Components Analysis

Find dimensions that explain the maximum variance with the minimum error

A useful tool for data reduction

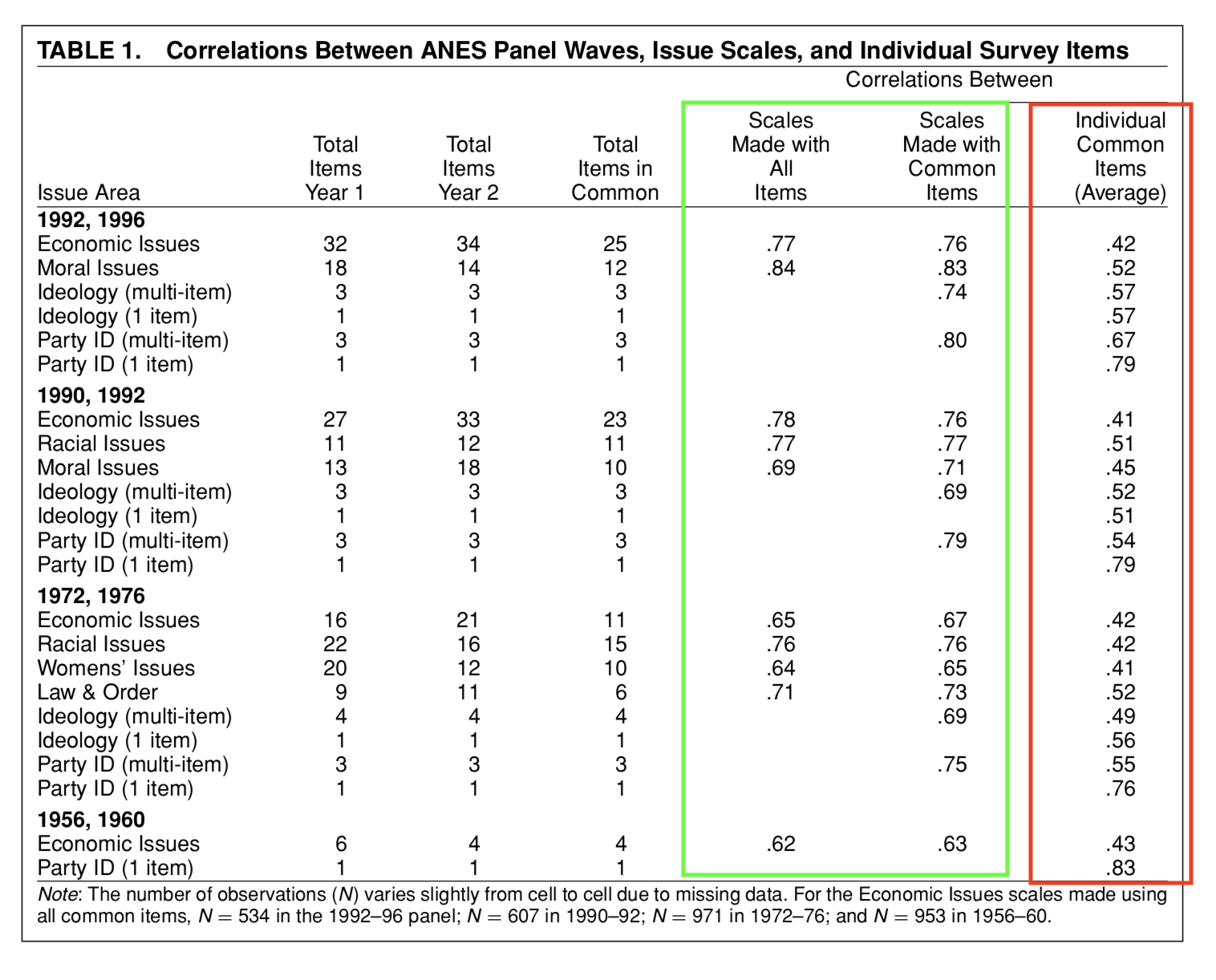

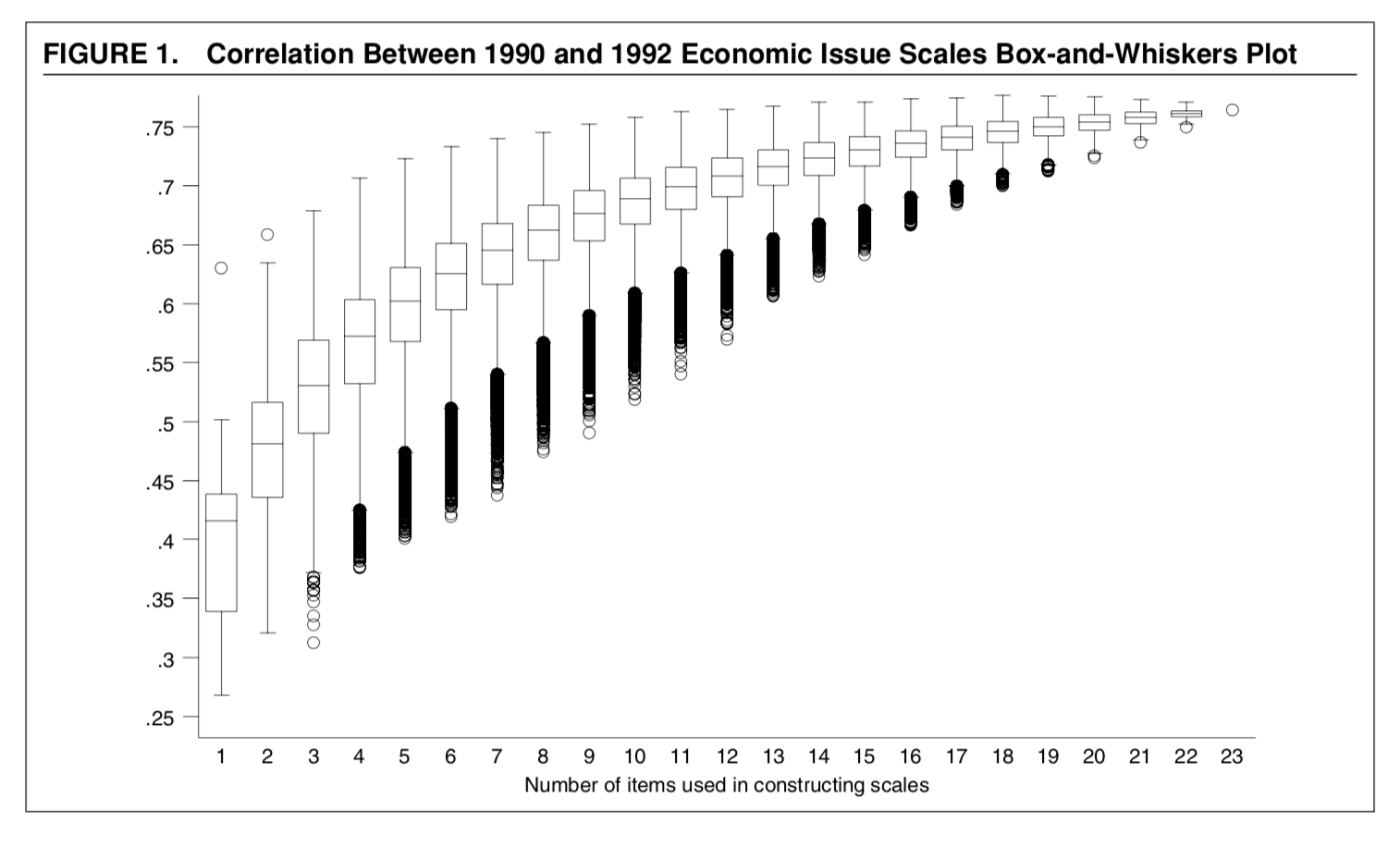

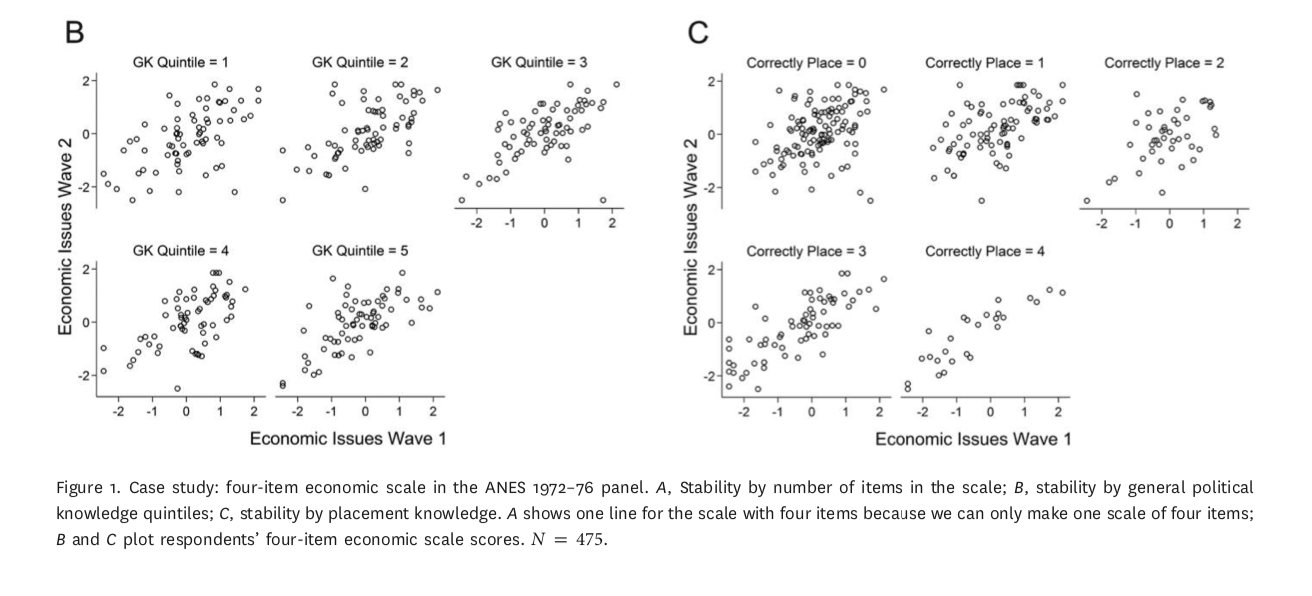

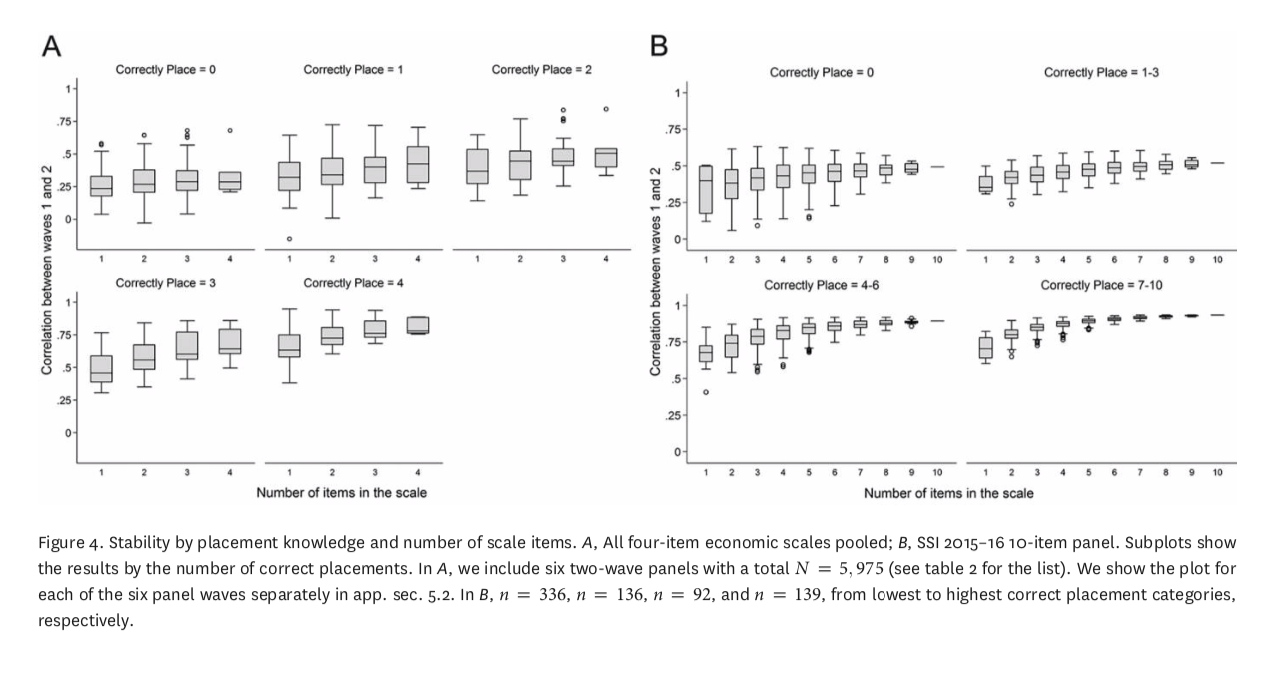

What’s are the results

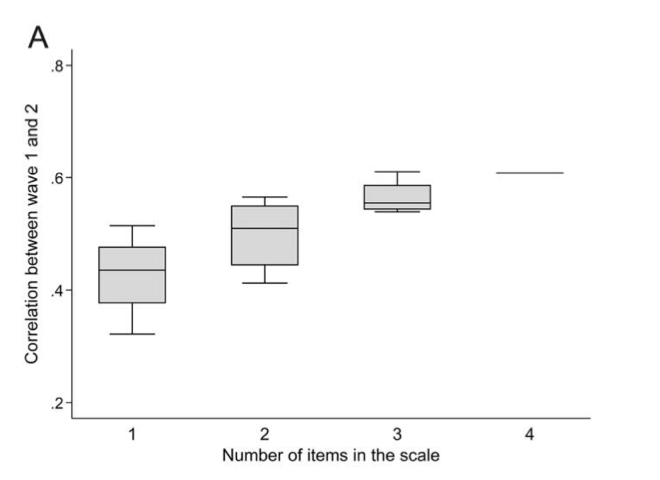

- The over time reliability of of scales increases with the number of items used

- Table 1, Figure 1

- Table 1, Figure 1

- The correlations are higher between scales within surveys

- Table 2, Figure 2

- Issue scales are more stable than policy predispositions

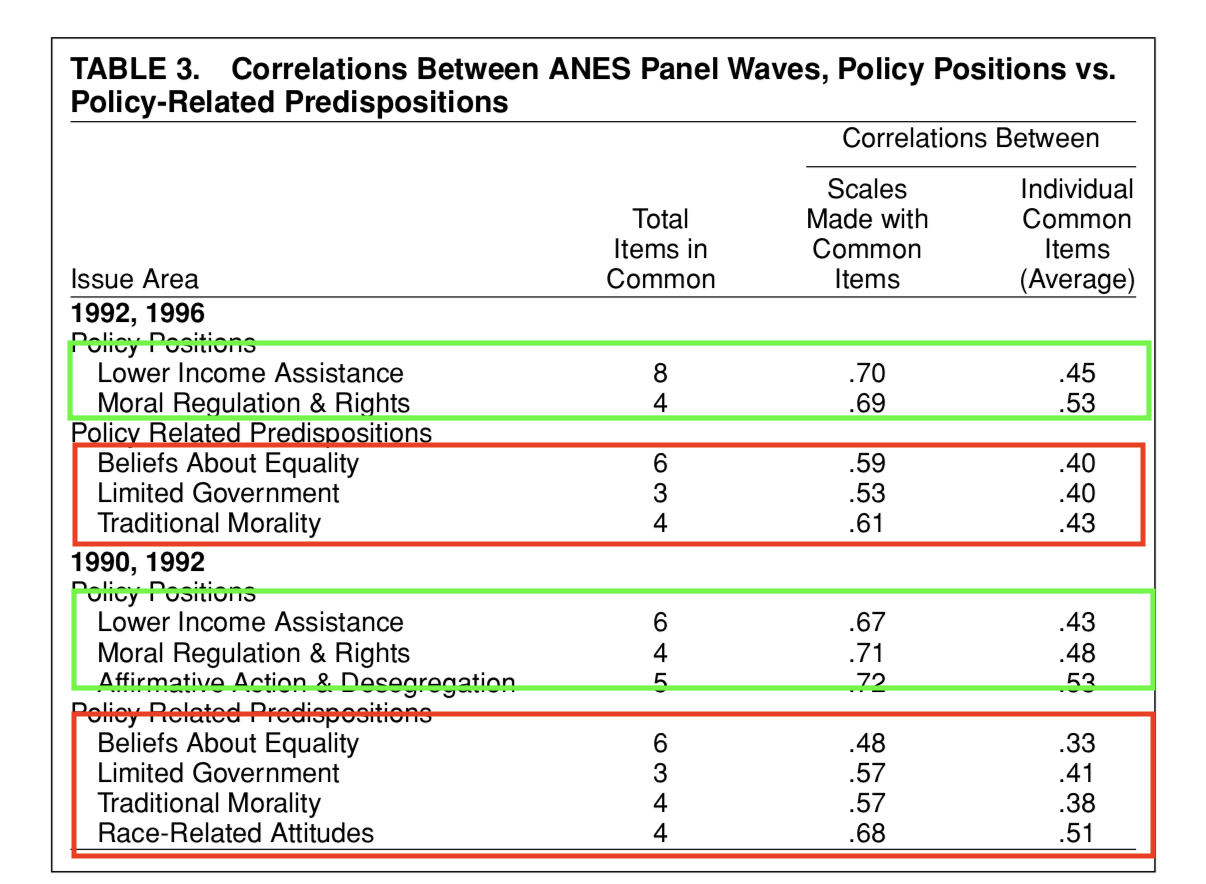

- Table 3

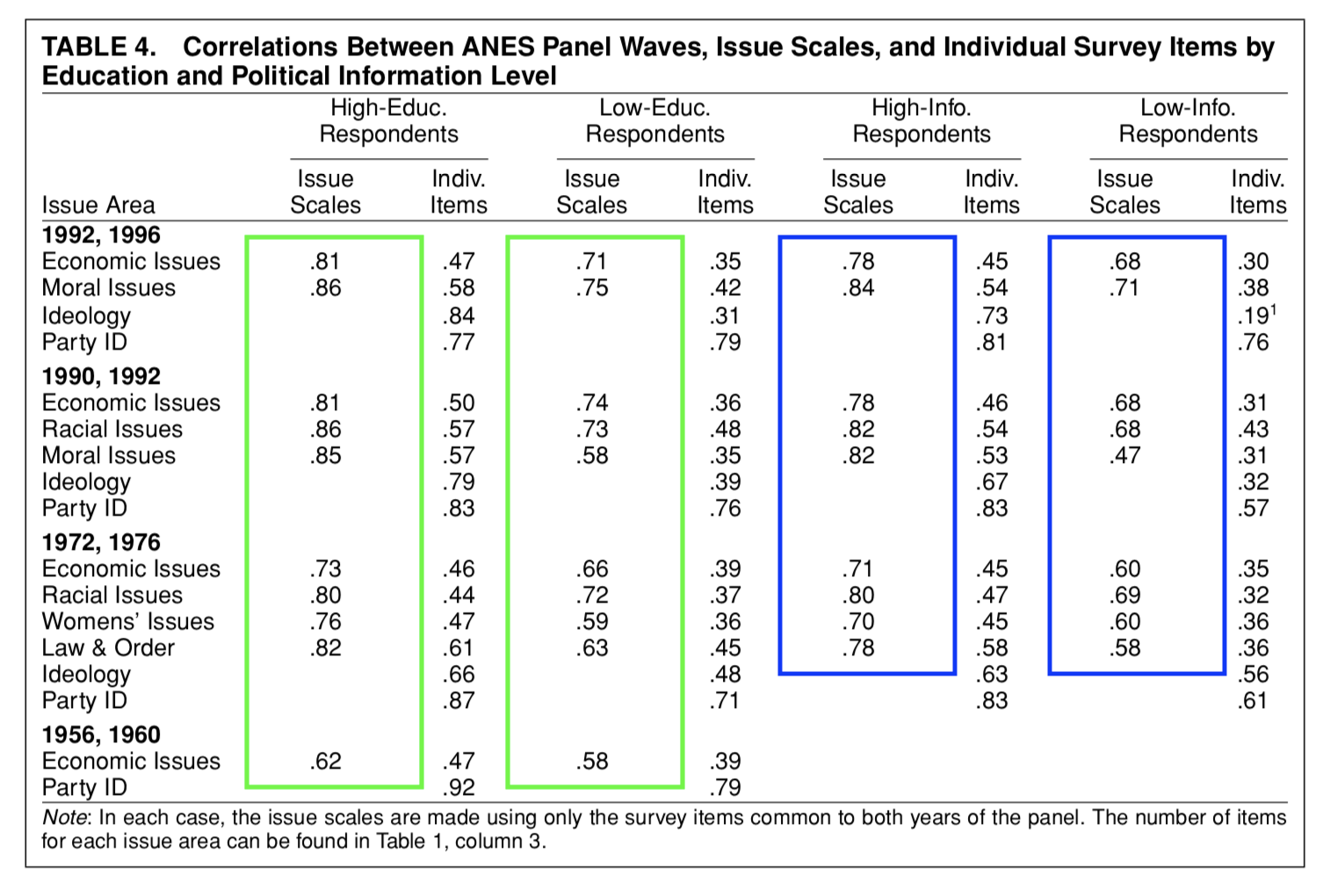

- Little variation across political sophistication

- Table 4

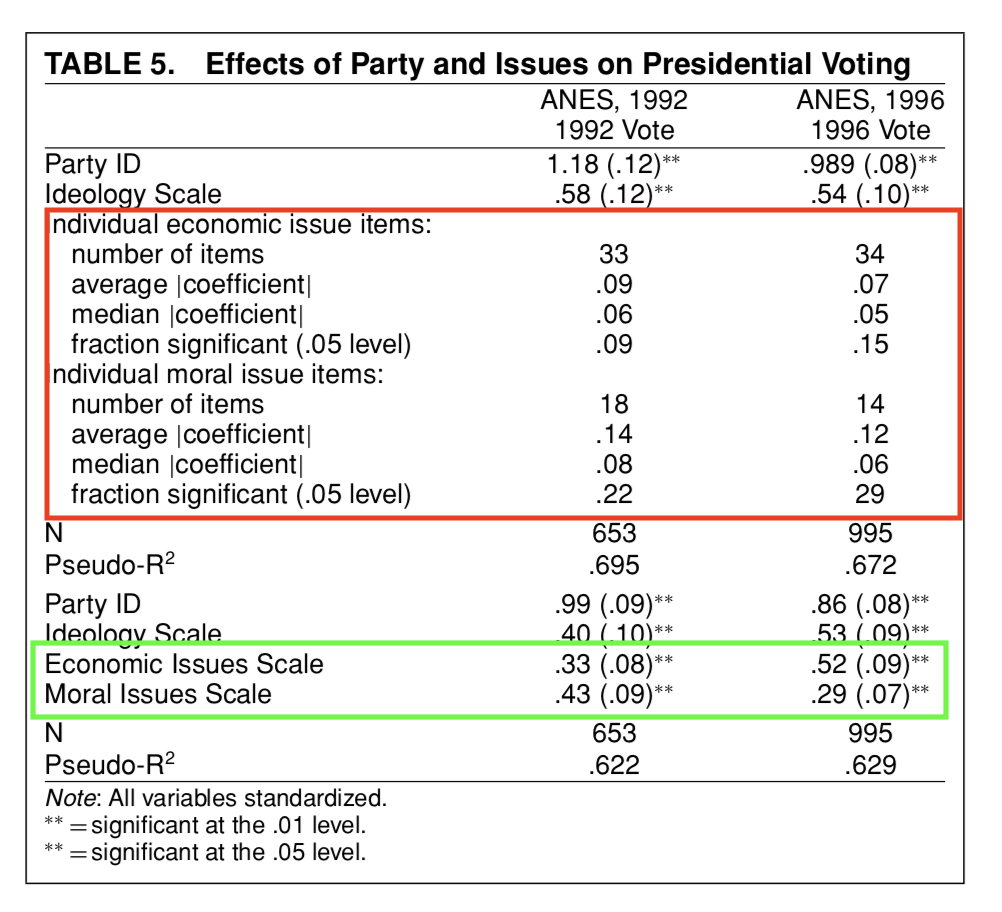

- Issue scales predict vote choice

- Table 5

The over time reliability of of scales increases with the number of items used

The over time reliability of of scales increases with the number of items used

The correlations are higher between scales within surveys

Issue scales are more stable than policy predispositions

Little variation across political sophistication

This is in contrast to what Converse’s “Black and White” model would predict and consistent with general arguments about measurement error

The entry point for Freeder et al.’s critique

Issue scales predict vote choice

What’s are the conclusions

Democracy is saved?

It’s the measures not the public that’s the problem

Use multiple measures and scale them together to study the concepts we’re interested in

The importance of political sophistication may be overstated

Freeder et al. (2019)

What’s the research question

- Is the lack of ideological constraint really just a function of measurement error, or is it a product of citizens’ ignorance of “what goes with what”

What’s the theoretical framework

- Measurement error critiques of Converse like Ansolabehere et al. can’t distinguish between error due to:

- The vagaries of the question (classical measurement error)

- The vagaries of person (lack of knowledge)

- The vagaries of survey response (more on this later)

- Averaging reduces error from all of these sources

What’s the theoretical framework

- Knowledge of what goes with what (WGWW) measured by awareness of which party is more liberal or conservative explains lack of constraint, even after accounting for measurement error

What’s the empirical design

Panel data with multiple issue items, measures of general knowledge/sophistication, and specific measures of WGWW proxied by candidate and party placements

Correlations and scale properties

Sub-group analysis

Regression analysis

Simulations

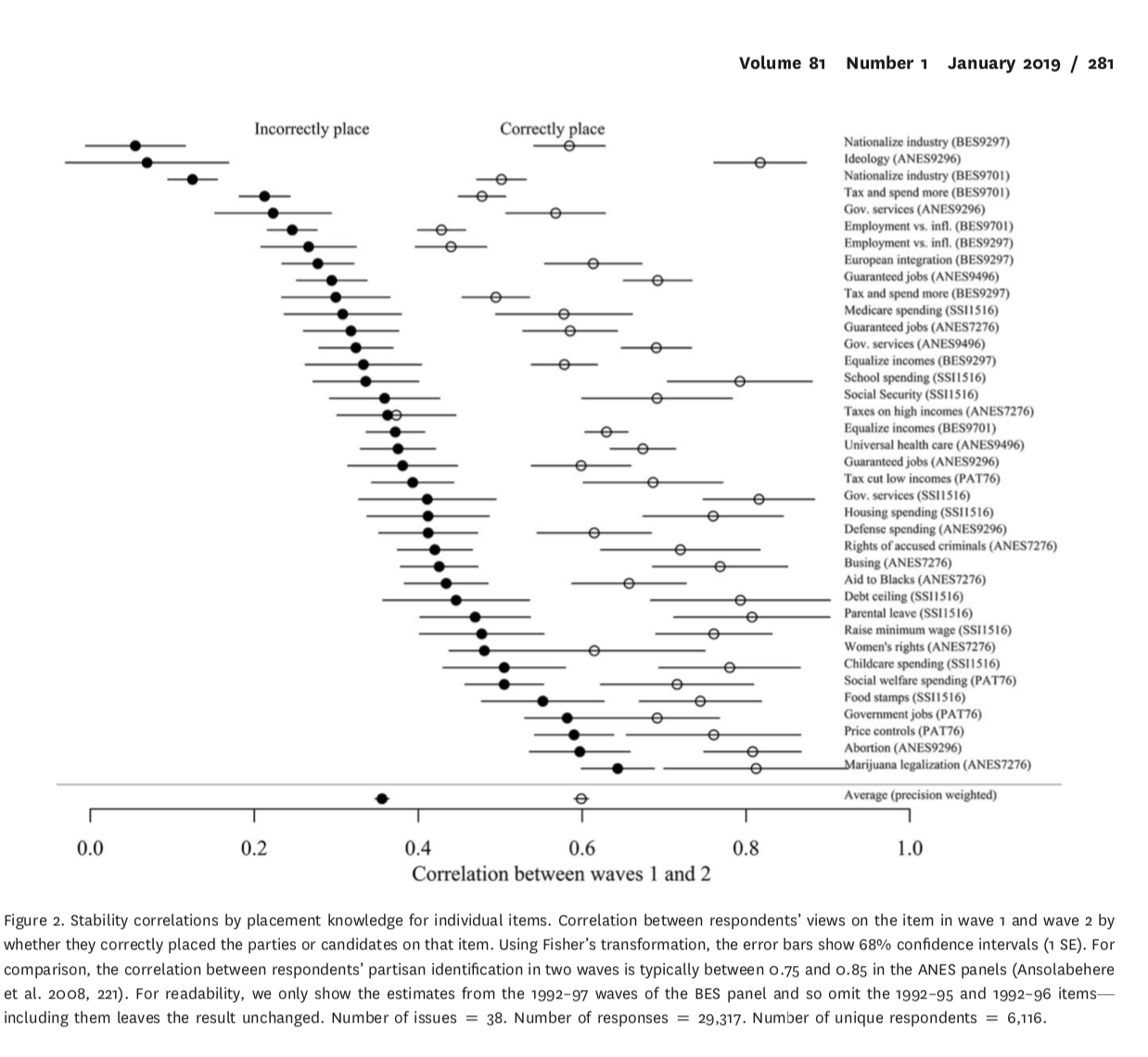

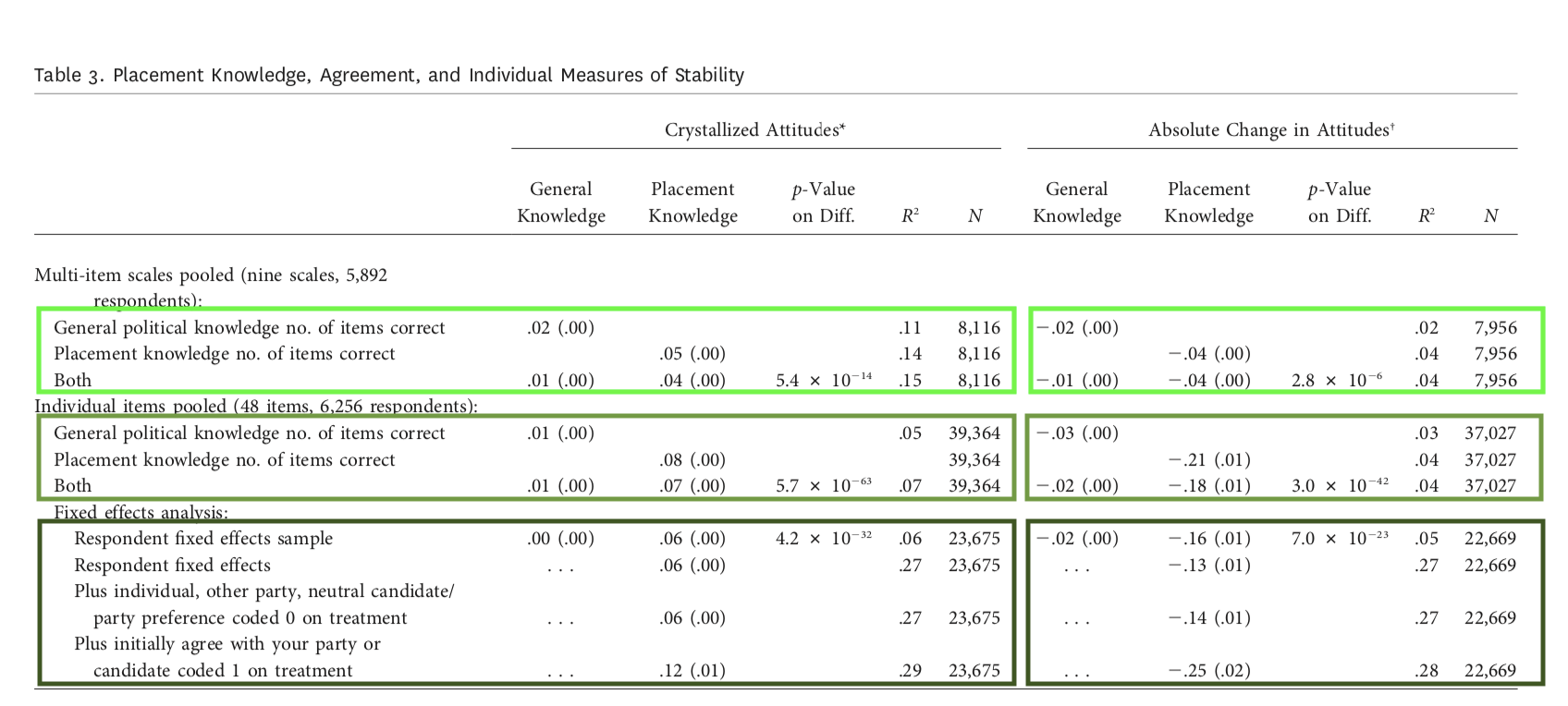

What are the results

More items reduces measurement error

Constraint doesn’t vary with general knowledge, but does vary with WGWW

True of scales and individual items

WGWW predicts attitude stability

But only for people who agree with their party’s positions

More items won’t fix the problem

More items reduces measurement error

Constraint doesn’t vary with general knowledge, but does vary with WGWW

True of scales and individual items

WGWW predicts attitude stability

But only for people who agree with their party’s positions

More items won’t fix the problem

What are the conclusions

Correcting for measurement error alone won’t save democracy

Multiple items are still useful

- But what does the first principal component of a multi item scale really mean?

Where does knowledge of what goes with what come from?

- Are parties the only source of constraint?

References

POLS 1140

Social Groupings as central objects in belief systems